On November 25, 2019 my hometown ceased to exist. The citizens of what had been the Village of Amelia, Ohio for 119 years voted to dissolve their community over a 1% increase in income taxes.

Now, as one of Amelia’s native sons, a graduate of its schools and — at one time — a fairly active young citizen it was weird for me to wake up last November and no longer have a hometown. It’s a strange thing to grieve. It has no impact on my life anymore, but it’s surreal.

So I decided to talk to some of my friends, classmates and neighbors about their memories of Amelia and its legacy…

Denise Rivera (Class of 1984): The Amelia of my childhood was very family oriented, very community oriented…we had a cow in our backyard, our neighbors had horses when we were growing up. So, it’s really changed, it was very much…I would even call it a farming community when I was a kid

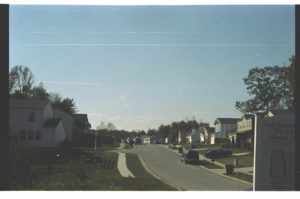

Stacy Recker (High School Teacher, 2002-Present): Like thriving and small town and really close-knit until like the ’80s, and then it sort of suffered this economic turmoil…I feel like Amelia didn’t necessarily have an identity, which is fine when State Route 125 was a horse route and you were using that to get out to the country and it is a wide spot in the road. And it’s maybe a spot where you rest your horses or exchange something or whatever…but yeah, it’s not a bustling place.

Wesley Teel (Class of 2011): My husband and I would joke about it. That we would drive through and say “Ope! We’re in the village! Ope! We’re out of the village!” Because its just so small…

Bobbi Gordon (Class of 2012): I never thought of it really as a city…or a town. And Main Street never really had much besides the elementary school, the bank that got robbed when we were in elementary school and a Dollar General, I think.

Trent Wirth (Class of 2011): Then all of these various neighborhoods, whether they were collections of townhouses or condos or big sprawling suburban neighborhoods…and each neighborhood kind of said something about how much money you had. I think we either became more aware of that as we got older or it just became more real as we got older.

That division Trent mentioned came up a lot. The mix of farmland and suburban subdivisions past Main Street clearly marked the divide between the area’s older Appalachian families and newer arrivals who moved in during the 1990s and early 2000s…

Stacy Recker: It’s a classic Appalachian culture mixed with a suburban culture…

Denis Rivera: My kids said Amelia, this was their analogy, was “The Haves and the Have-Nots.” And not that you were rich, but that you were comfortable and you could afford to do things or you didn’t. And the same went of the parents, either you cared or you didn’t. And I think socioeconomically those were the same two groups.

Wesley Teel: If you lived in this place in Amelia, you knew who you were. You knew the status that you had. And if you lived in another place, you knew the status you had. Like, I was definitely a Have-Not…and I knew it, because I could look at the people who were Haves.

Bobbi Gordon: Oh, we were the poor kids. I think they’d joke about it, they were always like “Oh, it’s just Amelia, y’know…” or like “Oh, it’s okay, because we’re Amelia kids…”

Trent Wirth: My mom did a really good job of making sure that even though se was a single mother and raised us on her own for a long time, that we never really felt poor. But looking back, I was poor. There are pieces of that that you don’t want to remember, like being home alone a lot. When you were probably too young to be home alone, but you didn’t want to be at day care so your mom just let you be home.

The one thing we all had in common was school. Our schools were old, some of them dated back to the 1930s. They didn’t have air conditioning or matching chairs and desks. But all of that contributed to our scrappy sense of pride…

Bobbi Gordon: I would never want my kids to go to school in a building like that now looking back on it. I mean it was what we had and it was fine and we all enjoyed it, but it was just falling apart.

Trent Wirth: There was hole in one of the classroom walls, they were brick walls, and you could push a pencil through it and then go out during recess and get your pencil outside. And looking back that seems like probably a problem that there was a hole in one of the walls.

Stacy Recker: Yeah, it was amazing…I totally understand that it was…obviously it had asbestos and I think it had some lead in there and it would have cost a fortune to upgrade it.

Trent Wirth: Amelia High School felt scrappy, which I don’t know, it’s like this underdog kind of theme that I’ve got going…Playing sports at Amelia High School we were always the underdog so it was always really awesome if we won and just kind of okay if we lost.

Denise Rivera: It was very much a rival school with Glen Este, I mean that was very much alive…And it was more of a competitive “We want to win because we want this bell…” which meant nothing in retrospect, but it was all about winning the game. Where I felt like when the kids were in high school it was more of a hostility.

But much of that cohesion was lost when Amelia High School was merged with our rivals at nearby Glen Este High School in 2016 to form the West Clermont High School. By that point what remained of a village identity was mostly gone…

Stacy Recker: And so I think it was more so the older generations who had so much of that identity of Amelia or Glen Este that really made it contentious and “How are we going to do this?”

Denise Rivera: There wasn’t pride in, I don’t think, either of the schools…not the kind of pride that we had…and so maybe by bringing the schools together in a new building with new state of the art things that it would push more people to have a desire to learn and to actually be present at the school.

Bobbi Gordon: While I still think there’s some white trash-y vibes because everyone is like “Oh, it’s Clermont County. Oh, it’s West Clermont.” I think that the community as a whole seems more proud of it, because it’s kind of a community center and we’ve never really had that before.

The controversial income tax arose as a ballot proposition shortly thereafter and with it the rumblings of a dissolution. When the villagers went to the polls last November 64% of them decided there was no need for a village anymore.

Denise Rivera: I don’t think the elected officials held themselves in good light during the debates and I think the residents let their redneck side fly.

Wesley Teel: People just didn’t Todd. They didn’t like the mayor. And they just wanted to find a reason to get rid of him. And as soon as the high schools merged that was kind of the key hit-off point…

Denise Rivera: I think that the village, the people who were running the village, took some liberties that they probably shouldn’t have. And I think that gave a distrust for the village.

Wesley Teel: I remember hearing rumblings about how it had changed everything and it was going to cause the dissolve, and then silence…It was like the most non-monumental thing ever. Like, “Oh! We’re not a village anymore.”

Trent Wirth: And like the community that had been built up around kickball and tag started to fade away. It’s funny because it feels like it evolved not disappeared.

Denise Rivera: It feels about the same as not having the high school that I went to. Like if you needed something from there, there are places where you can get it. But it’s just odd…y’know?

Stacy Recker: We lost one another. Whether you were an Amelia teach or a Glen Este teacher, you lost your people.

Bobbi Gordon: …she said something about the high school and Ben was like, “Your high school doesn’t exist! Your town doesn’t even exist anymore!” And I was like “Damn….you’re right…all of those things are true.”

Looking back, I’m not entirely surprised that the residents voted against the village. They never felt like they had a lot in common with one another. They were losing their sense of pride in the community. And I’m not sure I was ever too proud of it myself.

We didn’t realize we were living through the death throes until it was too late. Anything can break up a community without a shared sense of identity. In our case it just took an additional 1% in taxes.

Amelia was my hometown, but now it’s just a wide spot in the road. And maybe that’s how its meant to be.